If you have been granted access to the unredacted posts, please follow this link.

THE TRIAL for #81-21904.

The entire proceeding lasted less than four hours, notwithstanding the fact that the trial was divided into two days. The trial transcripts are made of only 265 pages. The jury was composed of four African American woman; one young Latino; and the Jury Foreman, a high end middle age white man (To my understanding, a retired police officer), who most probably controlled the end result of the jury’s deliberations. Three of the four black women were old, like over the age of 70. Two of them kept their gaze on the floor and were very shy or scared of so many police officers in the courtroom. The alternate juror was also an older African American woman.

It was obvious to me that the fact, that the so called “child victim” was related by blood to law enforcement agents, was very intimidating to most members of the jury. The fact that she was a cute little white girl, nicely dressed, must have melt everyone’s heart in that courtroom. She took the stand with determination and readiness. She was very calm and confident, probably because she had not been coached into lying. She had only been instructed to rely on body language, instead of on oral language, to comply with Assistant District Attorney Jeremy Akers’ key instruction: “Show the jury where Uncle Frank touched you.”

Referring to me as the child’s uncle was not an innocent error, but a very malicious strategy, because often the abusers are related to the victim. She answered truthfully by touching with her left hand her right shoulder and the right side of her waistline. She was done in about three minutes. She had a happy demeanor and smiled constantly. Assistant State Attorney Jeremy Akers provided the required statements for the trial transcripts to get me convicted: “For the record, the victim has touched her crotch area and her chest area.” That was a lie. Defense Attorney [REDACTED] had a legal duty to object to that lie, but he denied my request to do so, alleging that he knew what he was doing; and that the lie had not escaped the jury’s awareness. I was found guilty in less than ten minutes of deliberation, in part, based on those false statements, which can be confirmed with a copy of my trial transcripts. If that is not a fundamental error, nothing is.

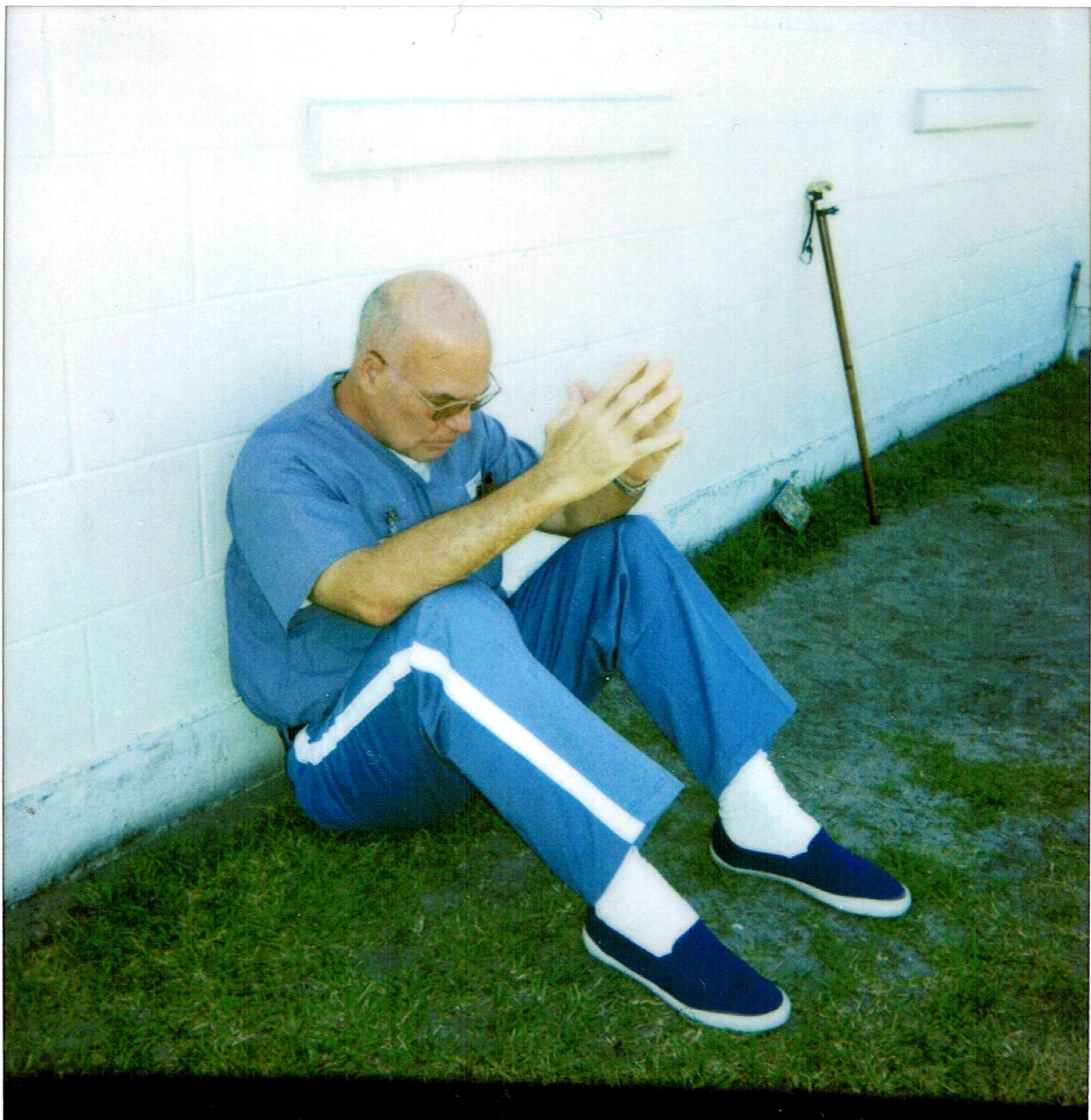

The betrayal of my court appointed attorney, Mr. [REDACTED], went beyond his refusal to object to the prosecutor’s misrepresentation of the facts, to obstructing my constitutional legal rights to testify against the false charge that I was facing. Today, that I know better, I hate myself for having allowed [REDACTED] to manipulate me. To keep me away from the witness stand, [REDACTED] asked the Judge for a recess in the trial; and took me to the men’s bathroom, where he aggressively insisted that: 1) We had already won the case, because the jury had seen that the prosecutor had lied. 2) That if I took the stand, the prosecutor was going to rely on my New York City manslaughter conviction to persuade the jury to change their minds and find me guilty; 3) That due to my facial paralysis, I gave out a very sinister appearance that made me look like a sexual predator and like a criminal. 4) That I had ignored his orders to dress up with light colored clothing. 5) That if I continued insisting on testifying on my own behalf, he was going to withdraw from the case and leave me on my own.

This last threat ended up the ten minutes argument, because I didn’t have the required legal knowledge to represent myself. I erroneously surrendered to [REDACTED]’s manipulation. Years later, I realized, through reading law books, that in such cases, if the defendant fails to declare to the jury his undiluted innocence, most likely, the jury will agree with the prosecutor. It was imperative for the jury to hear from my mouth my side of the story. If I had testified, I would have obtained justice and won my trial.

I should have realized that fact during my trial, because during the voir dire proceeding, I witnessed a long 20 minutes argument between Judge Steven D. Robinson and two of the jurors, the young black girl and the young Latino man, who placed the judge on notice that, if I failed to take the stand, they had no choice but to find me guilty as charged. They did not care about my legal rights to remain silent, and they made that argument to the judge many times. That was the argument on which I relied to try to convince Attorney [REDACTED] to allow me to defend myself on the witness stand. My attorney knew, or should have known, that by blocking my access to the witness stand, he was intentionally causing me to be convicted of a crime that not only I had not committed, but that never even existed. No crime had taken place. R.R. had not been molested by anyone. Years later, I wrote a long letter to Mr. [REDACTED] to address these facts. He never answered me.

[REDACTED] was called to testify. Basically, [REDACTED] provided an honest testimony, but the jury ignored it. She didn’t deny her role in inculcating the idea of sexual abuse in R.R.’s impressionable nine year old brain.

The detective that Sgt. Haar had sent to my house (Named Mr. Marshall or something like that), also took the stand. His only lie, as far as I can remember, was that I had told him that I had asked R.R. to accompany me in the van, which is not true. R.R. had made the original request and my wife had asked me to let her ride with me in my van. His obvious objective was to provide the inference of a guilty mind. I am grateful that he didn’t lie beyond that.

My brother George also took the stand, only to contradict the detective’s lie. George had witnessed the entire conversation between me and Detective Marshall.

TO BE CONTINUED

Frank Fuster.